An essay I wrote. It was supposed to be based on any book that had to do with an individual's struggle with a disability. I chose George Weigel's "Witness to Hope."

Dignity at the Heart of Disability: John Paul II and the Heroism of Service

“But if there be truth in me, it should explode. I cannot reject it; I would be rejecting myself”

--Karol Wojtyla (John Paul II)

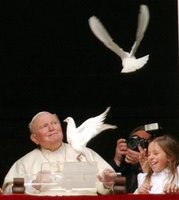

When John Paul II walked on stage one did not see the man overcome by the shadow of disability, but disability outshone by the man. He slurred and slobbered, his hands trembled, his feet faltered in a shuffle until they could shuffle no more. In the end, the Parkinson’s disease transformed what many regarded to be a handsome, rugged and radiant face, into a slack mass of drooping skin. He had become a living, moving portrait of human sadness. Yet where the disease could ravage his body, it could not lay claim to his soul. The “sadness” in his frozen face remained skin deep. Further in, beyond what eyes could see and diseases could reach, a deposit of faith continued to sustain the man George Weigel considered the 20th century’s great “Witness to Hope.”

For many, John Paul earned this title even though many in his condition would no longer accept hope as a livable reality. But those who know John Paul, and those who have followed his teaching and preaching for the past 26 years know that his was the “…face of a man lost in prayer, living a dimension of experience beyond words.” Disease and disability need not apply.

For many, John Paul earned this title even though many in his condition would no longer accept hope as a livable reality. But those who know John Paul, and those who have followed his teaching and preaching for the past 26 years know that his was the “…face of a man lost in prayer, living a dimension of experience beyond words.” Disease and disability need not apply.

This kind of heroism has been much needed because in a world of ready-made heroes. it’s been easy for true greatness to go unnoticed. We have been so eager to canonize those who, with Davidian courage, have “battled” against the Goliaths of disease and death. Yet these “heroes” are still defined by the disability they were victorious against, reacting against it rather than acting apart from it.

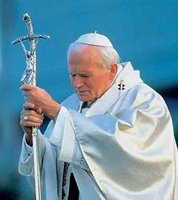

But it's important to consider that John Paul struggled not against disability nor against the body, but against the temptation to think that either is primary. He did not favor the Manichean notion that the body is evil. In fact, he considered the body good, even holy but only if united to a rightful spirit and offered for the glory of God. The icon of this offering John Paul held night and day in the form of his crucifix-tipped crosier and the price for it, he believed, could be borne in one’s very flesh.

This attitude and belief is part and parcel of John Paul's belief that the Church must be “led by suffering,” along the Via Crucis or “Way of the Cross.” He clearly heard what Jesus asked of him, “Take up your cross and follow me.” He did not take the invitation lightly even though he knew that it would not be a candied version of Calvary, a small cross and a short journey. It was to be a journey that would ultimately lead to his death in 2005.

But before then, many years of suffering were in store for the aging pontiff. Parkinson’s disease made its official debut in 1996. In the ensuing decade, the disease forced him to bow under its weight. He began to stoop profoundly, a large hump appeared on his back, and his movements turned slow and painful. No longer able to stand up from his chair or behind the altar to celebrate mass, John Paul was often transported through the vaulted doors of St. Peter’s Basilica on a customized moving platform that could hydraulically lower him on a built-in chair.

Although most of the world remembers him this way, he did not go gently from avid sportsman, actor and world-class thinker to slobbering octogenarian. This was a man, who barely ambulating, and in his 80’s insisted on climbing a spiral stone stairway at the Basilica of the Holy Sepulcher so that he could complete the Stations of the Cross.

Although most of the world remembers him this way, he did not go gently from avid sportsman, actor and world-class thinker to slobbering octogenarian. This was a man, who barely ambulating, and in his 80’s insisted on climbing a spiral stone stairway at the Basilica of the Holy Sepulcher so that he could complete the Stations of the Cross.

In spite of this vitality, there was no doubt that as the Parkinson’s progressed, John Paul did not like what it did to his body. But as always, his realities were brought into conformity with his convictions. That’s why at the Holy Sepulcher, he literally and spiritually did not run away from suffering. When he realized that it was his “vocation”, John Paul ran toward it.

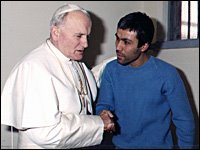

This was very evident to the doctors at the Gemelli Polyclinic in Rome from the1980’s until his death in 2005 Through a series of injuries and illnesses, that spanned two decades and 5 U.S. presidents, the world witnessed John Paul take up his cross again and again. In 1981 he was rushed to the Gemelli for a gunshot wound that missed his abdominal aorta, spinal column and major nerves by fractions of an inch. The wound led to the loss of over 6 pints of blood, an intestinal resection and subsequent complications that kept him in the hospital for almost 3 months. Later, he would be hospitalized for various viral infections, removal of a pre-cancerous tumor, gallbladder surgery, appendectomy, a dislocated shoulder, a fractured hip and finally for flu and Parkinson’s related breathing difficulty.

At the Gemelli, John Paul often joked about when the “Sanhedrin” would reconvene to discuss his case, and what they would decide to do. This took on both a facetious and more serious tone. According to George Weigel, John Paul once clarified to his doctors that the patient should be the “subject of his illness” not just the “object of treatment.” This distinction characterized John Paul’s focus on not just the body but the dignity of the person. This person could be him, an unborn child, a terminally ill patient or his would-be assassin, Mehmet Ali Agca.

John Paul engaged everyone including Agca with the full force of his personality. Though charming and by nature sweet, he was also impassioned to serve and impatient when he could not. Always given the choice to express himself, the pope requested anatomy lessons and step by step explanations. He was, after all, a one time quarry worker turned covert seminarian, a counter-cultural professor priest with a double doctorate, a mystic of the world stage who stood up against and survived two of the most oppressive -isms of modern times—Nazism and Communism. He was clearly someone who could take control.

John Paul engaged everyone including Agca with the full force of his personality. Though charming and by nature sweet, he was also impassioned to serve and impatient when he could not. Always given the choice to express himself, the pope requested anatomy lessons and step by step explanations. He was, after all, a one time quarry worker turned covert seminarian, a counter-cultural professor priest with a double doctorate, a mystic of the world stage who stood up against and survived two of the most oppressive -isms of modern times—Nazism and Communism. He was clearly someone who could take control.

However, John Paul's sense of " control" did not seem to reside in him or in the world around him, but in the world above. He believed in the provisions that God would make for the person of faith. He showed in his own body that these provisions could (paradoxically) consist of life-long suffering. Just as Christ offered the proof of his love in his crucified flesh, the disability of disease could be seen as a means to an end, a way to change faith into flesh.

This enabled identity that John Paul lived, his remarkable and timeless story, encapsulates the history of the Catholic faith. Ever mindful of the Church’s mystical roots, the great Carmelites, John of the Cross and Teresa of Avila, and Christ himself, John Paul elevated love by courageous words made real through courageous action. This is how he found dignity at the heart of disability.

This enabled identity that John Paul lived, his remarkable and timeless story, encapsulates the history of the Catholic faith. Ever mindful of the Church’s mystical roots, the great Carmelites, John of the Cross and Teresa of Avila, and Christ himself, John Paul elevated love by courageous words made real through courageous action. This is how he found dignity at the heart of disability.

Much of what John Paul taught and acted out in the great drama of his pontificate centered on the dignity of the person, not just his own, but that of everyone in every time and place. He taught that a person's dignified status is a privilege and a responsibility, an invitation to not only receive love but to give it. As a person with a very visible disability, John Paul bore witness to dignity in a public and personal way. He used suffering as a vehicle through which love would not only be spoken of but lived out, proposed and proven.

As Weigel put it, “What the Pope has proclaimed through his extensive writings on the right-to-life, he now proclaims by continuing his service despite crippling difficulties: that there are no disposable human beings; that everyone counts because Christ died for all; that those men and women the world deems burdensome or useless are human beings possessed of a dignity that cannot be measured in the coin of worldly exchange.” In light of his teaching and faith, it could be said that John Paul’s identity swallowed his disability.

Though it affected his walking, kept him off skis, and left him bent over, disability also became his Gospel in action. John Paul never agitated for the embryonic stem cell research that could someday deliver people like him from the clutches of Parkinson’s disease. For him, Parkinson’s was a reality, not something to be bargained with, nor something to trade in at the expense of human life. This unwillingness to made comparative decisions about the value of life (my life vs. an embryo’s life) made him a hero and champion for life and for lives affected by disability.

In cause of life and truth, John Paul was a serious man but the seriousness of his discipleship did not impoverish an indefatigable sense of humor. Even when Parkinson’s and arthritis led to the use of a cane, that cane soon became a metronome, pretend pool cue or twirling baton. It could also allow John Paul to poke his close, perhaps unsuspecting friends and entertain hundreds of thousands of endearing young Catholics. Through antics and in prayer prayer, John Paul showed that the disability succumbed to the man.

He was humorous and his humor remained. He was committed to the Church and that commitment remained. He was, by large consensus, a spiritual juggernaut, and this too did not change. His closest friends along with numerous heads of state, bishops, noted personalities, and countless people of every faith agreed that John Paul’s prayer seemed to move even the casual observer into a different realm of experience. He would groan, burying his head in his hands, moving effortlessly from the mundane to the mystical.

To truly understand John Paul’s response to disability or difficulty, it’s critical to understand how prayer shaped his life. It was not just part of his daily routine, but the punctuation of it, the capital letter, the exclamation point and everything in between. He would, as Weigel explains, make “all major decisions…on his knees before the Blessed Sacrament”, spending upwards of 4 hours a day in prayer while finding time to entertain guests, write encyclicals, read philosophy, meet with staff and travel 775, 231 miles to 129 countries in the course of his pontificate.

Many people are surprised to discover that Mother Theresa lived a similarly rigorous prayer life, spending many silent hours before the Blessed Sacrament, long before much of Calcutta could blink the sleep from of its eyes. Like her long time friend, John Paul II, the founder of the Sisters of Charity defended the dignity of persons, but only after drawing deeply from the well of prayer. From there both of these champions of life derived the spiritual energy and knowledge to improve the human condition from within and from without.

Many people are surprised to discover that Mother Theresa lived a similarly rigorous prayer life, spending many silent hours before the Blessed Sacrament, long before much of Calcutta could blink the sleep from of its eyes. Like her long time friend, John Paul II, the founder of the Sisters of Charity defended the dignity of persons, but only after drawing deeply from the well of prayer. From there both of these champions of life derived the spiritual energy and knowledge to improve the human condition from within and from without.

The essential message of human dignity, forged in war and oppression, and illustrated tirelessly in his own struggles, remains one of John Paul’s most important legacies. We can do well to learn what John Paul spent a lifetime teaching: “Nothing surpasses the greatness or dignity of the human person.” All who come to us bear the mark of their Creator, all reflect the “image and likeness of God.” We are challenged to recognize and to respond.

In living and in dying, John Paul advocated this person-centered approach of living. His teachings remind us to see more than the sum of body parts, and in fact, more than just a body. A person comes with a soul that is sometimes burdened, sometimes bereaving, often weary and always in need of healing. Thus persons deserve better than a casual nod, and certainly better than murder and malice.

John Paul taught that we deserve better, not because we merit it, but because God’s love demands it. The Holy Father defended this notion to the last, starting with the idea of knowable, unchanging truth: “Human history is a continual movement…but the Truth of Christ…lasts even amid changing events…thirst…long for Truth, tend towards it, seek it and reach it.” From there he reiterated a fundamental truth of Christianity, that dignity, service and greatness are inseparable. For John Paul, God is the common denominator. He is the dignity we see in others. He is also the dignity that allows us to serve them.

Faith in these principles of dignity and service allowed John Paul to prove that disability is not lack of dignity. He often cited the “essential criterion of…greatness” found in Matthew 20:26: “Whoever would be great among you must be your servant.” John Paul considered this line the summary of his calling. Even though it included long years of suffering and disability, he believed that his vocation served a purpose, that suffering is not wasted and that “In the designs of Providence, there are no mere coincidences.”

And yet I do not altogether die

what is indestructible in me remains…

what is imperishable in me

now stands face to face before Him Who Is!

--John Paul II

">

Categories: